-

The promise most aggressively sold alongside contemporary AI automation systems, particularly the emerging robotic workforce replacement industry, is not merely efficiency, but social continuity. We…

-

The story always starts with the same script: a breakthrough arrives, wrapped in the language of salvation, efficiency, modernity – some shimmering new substance or…

-

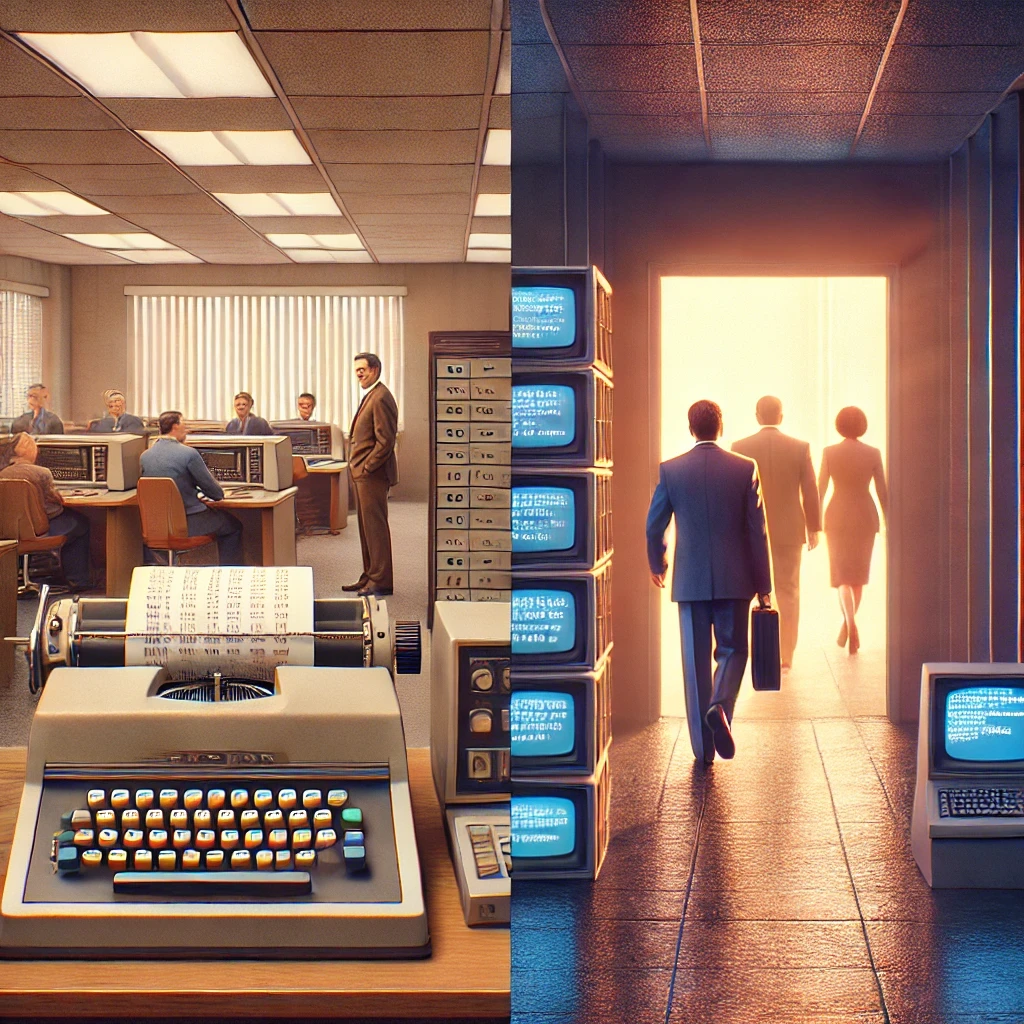

The Real Manufacturing Revolution in the Age of Dark Factories The promise of artificial intelligence has always been the same: liberation from labor through the…

-

AI is not the devil, rather the agenda and application of it in an area central to our cultural and intellectual identity.

-

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) has taken center stage in conversations about the future of education and creative industries. Promising effortless automation, personalized instruction,…

-

A montage of decades of culture, fictiona, real, and meme in the artistic stylings of Hayao Miyazaki, posted to Reddit The Eternal Return of Innovation…

-

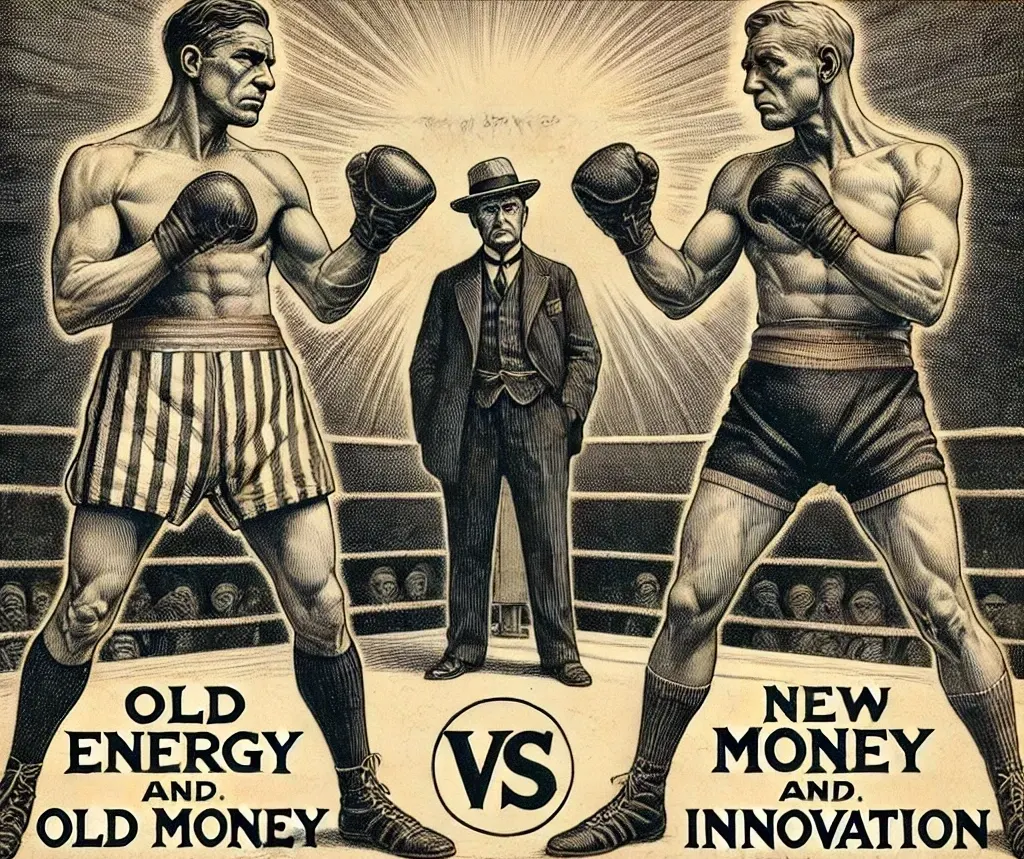

Introduction At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States experienced a radical transformation in its economic and social fabric. The nation had once…

-

Adapting to Rapid Change I. Introduction In every era, the intersection of human labor and technology undergoes a fundamental recalibration, often marked by cycles of…

-

Literacy, Inequality, and the Fight for Systemic Reform Introduction The COVID-19 pandemic was a catalyst for profound societal shifts, exposing deep-seated inequities in education, economic…

-

The transition from gas-powered vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs) represents a crucial element in global efforts to reduce carbon emissions and combat climate change. However,…