On the occasion I have been asked “What do you do for a living?” – for the last twenty years or so, my answer has been “I’m a technologist” (a phrase I first crossed in the writings of Cory Doctorow).

That answer may seem vague, perhaps even fanciful, but I see it as honest – it is the answer a painter, a sculptor, or a 3d environment rendering specialist might provide to the same question: “I’m an artist.” The answer I provide owes its genesis largely to my bread-earning – over the course of the last decade and a half, my paycheck has been tied to technology, specifically information systems and internet technologies. Despite the mundane aspect of this answer, the reason I reply with something less specific than the title tied to my paycheck is my deep-rooted passion for technology, and how it can be applied to make life better.

When this blog was in its pre-infancy, really just a series of conversations between J and I, it was this passion which fueled the topics we bounced between Those conversations gradually led us to the central aim of this blog – an explanation of the question:

In what ways has technology changed the world we live in, and in what ways will it continue to change it?

That inquiry is about as broad as my interpretation of the answer to “What do you do for a living?” It has also been well covered, by columnists and authors of greater experience or prestige than either of us possess. The exploration is boundless – it affects labor, ideology, theology, social norms, entertainment, language, education, psychology, science, humor – everything! In order to try and tackle a subject so immense, we decided we needed two things: a perspective of narrative, and a method of analysis.

When attempting to crystallize the many perspectives on technology into fixed pathways, and categorize the forms those perspectives tend to evolve towards, we took a page from Alexander Berzin (though neither of us are Buddhists), whose writings stipulate that all phenomena fall under three categories – destructive, constructive, or unspecified. The analysis of the constructive or destructive powers and repercussion will be the core of our conversation, with plenty of musing on the more ethereal nature of the unspecified. To ensure the thoroughness of our exploration, J and I will rebut each other regularly on our chosen perspectives. Additionally, it is our intent to develop and publish a lexicon of terminology related to key movements in technology, as well as the perspectives our pre-Industrial and Industrial revolution minds might have applied to our concepts.

As a lifelong pessimist, I chose the rockier of the two perspectives to focus on – I am going to generally concern myself with the constructive power and potential of technology. The unspecified phenomena, certainly, will be useful in the exploration of concepts and prognostication, but. lacking hard discernible measures of impact, will likely be ancillary, at best, in defending my position. The motivation behind my selection of perspective, I hope, will become clearer the more I write about the subject, but, for now, we’ll leave the modus operandi cloaked in the humorously glib phrase: “Hoping for Star Trek”.

As to analysis methodology, we hit upon what we both think is a fairly novel approach to looking at all these changes everyone has experienced or read about to some degree in the modern world we live in. The proposed method of our analysis led us to explore this potential, despite the aforementioned depth of writing on the subject. We are going to discuss these perspectives on technology using the springboard of writings, writers, philosophies and philosophers of the epoch of industrial revolution, in Europe, then later the United States, then, even later, Japan, Russia, India, and China.

It is our initial research into this wealth of perspectives and writings which led us to the name of this blog, tritely abbreviated in a most modern method. The phrase “Contemporary Reactions to the Machine” is from an essay by Thomas Carlyle in the 1873 Edinburgh Review entitled “Signs of the Times”. Though Carlyle’s views are largely contrary to the view I mean to defend in looking at the breadth of modern technological phenomena (he was quite concerned about the negative and visible side-effects of the industrial revolution), even in my opening research, I found evidence supporting my perspective in his work:

Know’st thou Yesterday, its aim and reason?

Carlyle’s (and others) attribute to Goethe

Work’st thou well To-Day for worthy things?

Then calmly wait the Morrow’s hidden season,

And fear not thou what hap soe’er it brings.

This is a hopeful little rhyme, suggesting full understanding of the past and present is not necessary to the success of a better tomorrow. When I went to look for the contextual publication of the original piece online, I came upon an article from a 1920 volume of The American Journal of Philology, which explains, in several pages, that the original author of the cited text was not the well-known German genius, but, in fact, should be attributed to a French literary figure, François de Maucroix , who pre-dated Goethe’s birth by a considerable window.

When trying to come up with an example of the constructive power of technology, a contemporary reaction to the machine emerged – one of Wonder. This Wonder comes, in part, as I consider the contextual search leading me to refute the popular citation of Carlyle’s times to a similar search I might have done thirty years ago. Aside from being specifically tied to geographical proximity to a collection that might have the original article, in addition to the Journal clarifying the origin of the verse (or the patience to write and receive a number of letters to determine the matter), the simple retrieval of the pertinent details, even by a well-versed research librarian of thirty years ago would have taken far longer than a few typed words and mouse clicks it took me earlier today. Beyond that initial information retrieval, in a few more clicks, I had a fair approximation of a general (Wikipedia) knowledge base on the key players, as well as a stable of additional resources and footnotes to follow up on.

Take this same search back twenty years, before the establishment of clear-cut online information resources, and I might have been able to garner some leads myself from a CD-ROM-based encyclopedia, or some basic reference material available through a BBS or Usenet node. It is possible that I may have been able to find the text of Carlyle’s article on Project Guttenberg, or a similar repository of pre-Creative Commons digital publications, but that is fairly unlikely, given the esoteric nature of the subject matter.

In all, this illustration has not proven that technology and progress are positive forces more so than negative ones, nor has it done anything to lessen or deflect the easily quantifiable destructive aspects of these items (as I am sure any printed-on-dead-tree Encyclopedia publisher of yesteryear would be fast to point out). What my example has done is provide a simple and direct example highlighting the speed with which information can be shared, ingested, analyzed, regurgitated, and acted on, with a fair level of sophistication. Indeed, the platform on which these thoughts are being published and shared is a byproduct of this age, and you, dear reader, are a participant in it!

“Must go faster, Must go faster!”

Ian Malcolm, Jurassic Park

None of this exposition is taking into account the myriad of other research options I had related to self-published website sources, or multimedia sources I could have accessed through free or paid sources. Similar acts of research and learning are taking place at a nearly incomprehensible rate, simultaneous to my own, on subjects both weightier and more meaningful than my meager example. To add further amazement to my pyre of Wonder, I am not even citing or referencing the “best” tools available with which to augment my store of knowledge – simply the free and readily available ones I can get to with minimal interaction.

Though his observations are a bit hyperbolic, and tied far more to the physical experiences of technological advances, as opposed to the informational research experiences, I’m forced to agree with comedian Louis C.K. on the popular perspectives and lack of Wonder at the technology all around us, which, contextually, we tend to take for granted:

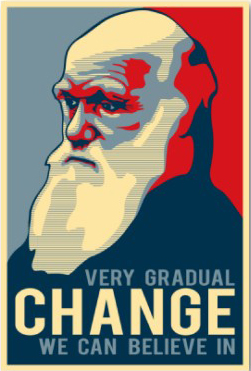

Western society, particularly it’s historians, have been quite fond of establishing decades, centuries, ages and epochs to quick-reference blocks of time for generalized discussion of progress. The era preceding the Industrial Revolution in England (the 18th Century) was named by critic Donald Greene “The Age of Exuberance” – it was a time of turmoil between classical genres of writing, and new forms, meant to entertain and inform, sometimes doing both at once. The artwork, above, is an echo of this time, where an artist felt that an oil painting, normally reserved for veneration of religious or political figures, would be an excellent medium through which to express their awe and appreciation for the advances in learning and science.

The challenges in form and method throughout the Age of Exuberance were mirrored by the content those forms dealt with – satire and novels challenged deeply ingrained societal constructs and traditions. These charges against literature and society in the Age of Exuberance promoted paved the way for the sweeping technological and social changes of the Industrial Revolution. I see many parallels between that time, and the neo-technological society which led to the birth and rampant outgrowth of the Internet – and I see those parallels extending into the echoes that follow that era – times of great societal upheaval and technological advance.

I hope, someday, people will look back at the near-miraculous accomplishments achieved within a mere two decades (to say nothing of what potentially lies ahead) and refer to it as “The Age of Wonder” – for we are truly in a place and time like none other before us, which, hopefully, will pale before the times technology will bring us to beyond tomorrow’s sunrise.